Hominid Species Time Line

Page 30

Homo neandertalensis:

The species that forced a radical reconsideration of human origins; lived from @ 300,000 years ago to 28,000 years ago—perhaps a remnant survived longer than that in Spain.

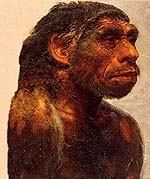

The skull cap above, found in the Neander valley of Germany in 1856, was one of the first fossil finds of early humans. Since the remains were discovered before Darwin published On the Origin of Species (1859), contemporaries had no conceptual frame for understanding what they had discovered. Instead, they glibly explained the bones away according to their racist notions. Nevertheless, the Neanderthal bones eventually forced a radical reconsideration of human origins.

The Neanderthals remain something of a mystery in the story of human descent. Scientists long believed they were a closely related sub-species of modern humans and for a time classified as Homo sapiens neandertalensis. In 1997, however, a team of American and German scientists isolated a small strip of DNA from these original German specimens. They found that modern human DNA differed more than expected from the Neanderthal DNA. The conclusion—still tentative because based on a single piece of evidence—is that Neanderthals represent a collateral line of late Homo heidelbergensis, related to but not ancestral to modern humans. The differences were great enough to make interbreeding appear impossible, though hybrids with modern humans may have occurred. A recent discovery of a juvenile in southern Spain looks as if it might be a hybrid.

Homo neandertalensis—"Neanderthal Man"—was a robust human species occupying Europe and western Asia during the recent ice age. Though they also flourished in warm interglacial periods, they were the first human species to learn to survive in the challenging conditions of glacial advance. The Neanderthals survived by hunting the largest and most formidable Pleistocene mammals—the mammoth, wooly rhinoceros, and wild cattle. Analysis of their bones shows that they were almost exclusively meat eaters, like lions and wolves. They competed with these large predators in an extremely harsh environment. Many individuals show evidence of broken bones, particularly limbs and ribs, so their life style was not an easy one.

Below are several artists' depictions of Neanderthal life in ice-age Europe.

|

|

Even though they fascinated us, our earliest views of Neanderthals defined them as primitive and crude, rather like Homo erectus and quite different from modern humans.

Their arm and leg bones are, in fact, approximately twice as thick as ours, suggesting both their immense strength and the rugged conditions of their existence. Otherwise, their bodies are strikingly modern. They had prominent noses, long, forward-thrusting faces with sloping foreheads and big skulls. Their average brain capacity (1400-1500 cc) actually exceeds that of modern humans. Though large, the configuration of their brain is different from ours. The speech areas of the Neanderthal brain are not as developed as ours, and the forebrain is smaller.

Remains of over 300 Neanderthal individuals have been recovered, and they exhibit a great variety of individual characteristics. The skull at left, dated 35,000 to 53,000 years ago, shows a distinctive pattern of wear on the teeth, suggesting that this individual wore down his teeth in an continuous, strenuous activity such as processing hides by chewing in order to make them pliable enough for clothing. If so, this would be the earliest indirect evidence for clothing.

The tools above right are characteristic of Neanderthal culture (Mousterian.) They had an effective but fairly simple tool kit which changed very little over the life-time of the species. This contrasts sharply with the rapid advances made in technology by early modern humans. For example, no needles have been found associated with Neanderthals.

As we learned more about this species, they began to appear less alien to us. “Artists’ conceptions” provide a good history of these changing views. Early paintings show Neanderthals in a bent-kneed stance suggesting an imperfect or only partly erect posture; the head is set forward on the spine much like that of a chimp or gorilla, and they are depicted as having clumsy, extremely hairy bodies.

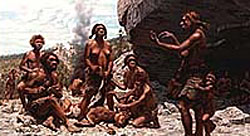

The painting above illustrates more current knowledge of Neanderthal anatomy and offers a tentative reconstruction of their social life. Here at a cave site in what is now the Czech Republic, a mature female oversees the distribution of food to an extended kinship group. Instead of a stooped, debased, and brutal ancestor, these Neanderthals are depicted as close cousins of modern humans—a separate subspecies but nevertheless "Homo sapiens" like ourselves.

Evidence of cultural practices and a complex social life

Neanderthal sites often reveal evidence of cultural practices. A Neanderthal cave burial near Dordogne, France, contained a body buried in the fetal position with tools and food; a bear skull lies at the edge of the grave. Flower pollen found in the grave suggests that medicinal plants were scattered over the body as well. These practices obviously suggest complex beliefs and rituals.

Some Neanderthal individuals lived to middle age or older, and we have a few examples of adults who had suffered crippling diseases or injuries yet were cared for in middle age. The two upper arm bones at right are from a male of about 45 years of age from Shanidar, in Iraq. The left arm is completely withered from an early injury or disease. The fact that the individual with an injury this severe survived into a relatively advanced age implies the existence of a complex social life in which other group members would have shared food and other life-supporting tasks. This individual must have contributed something other than physical strength to the social group in which he lived.

Some Neanderthal individuals lived to middle age or older, and we have a few examples of adults who had suffered crippling diseases or injuries yet were cared for in middle age. The two upper arm bones at right are from a male of about 45 years of age from Shanidar, in Iraq. The left arm is completely withered from an early injury or disease. The fact that the individual with an injury this severe survived into a relatively advanced age implies the existence of a complex social life in which other group members would have shared food and other life-supporting tasks. This individual must have contributed something other than physical strength to the social group in which he lived.

It is not clear whether Neanderthals had a developed language, but there is evidence of significant cultural development.

Neanderthals overlapped and co-existed with modern humans in the Near East for @ 50,000 years. They disappeared, however, shortly after modern humans appeared in Europe. It is not clear whether Neanderthals were out-competed by our ancestors and directly exterminated, or absorbed into the gene pool of modern humans. The first possibility appears most likely, given present evidence.

References:

Homo neanderthalensis on TalkOrigins.org